By Jack Marley

Fluxus is a hard thing to define. It would be easy to call it an artistic movement. However, many of its central figures clearly said that it wasn’t. They also continuously rejected the artistic establishment which seeks to categorise art history into movements. To call it one, then, would be missing the point. Owen Smith provides a helpful alternative to get to grips with the phenomenon of ‘Fluxus’, arguing that the term refers to two things: its participants’ attitude towards art, and the historical moment of their activity. Considering these two aspects is a good way to answer the question of what Fluxus is.

- Read: Scariest pieces of classical music: the 5 most dangerous pieces

- Read: John Cage: 5 things you didn’t know about the experimental composer

Fluxus as a historical moment

Fluxus, in this sense, is generally agreed to have begun around 1962, when the first ‘Fluxus Festival’ was held in Wiesbaden, Germany, and ended in 1978 when the group’s ringleader George Maciunas passed away. Maciunas was central to Fluxus as a historical moment: he organised and produced much of the cultural activity that occurred under its banner across Germany and New York. By bringing together artists, venues, and audiences he translated a loose network of ideas and people into tangible events and publications. These activities were hugely varied, as this advertisement published in the first edition of Fluxus’ own

newspaper, January 1964, suggests: FLUXUS FESTIVAL IN NY MARCH-MAY street events, demonstrations, concert hall

events, film, music, wrvr radio program, exhibit tour, environments, bazaar, auction, feast, lectures etc.etc.etc.etc.etc.etc.

- Read: Profile of the Vegetable Orchestra | the troupe that carves instruments out of fresh produce

- Read: Profile of Pigstrument | an instrument designed to be played by pigs

This self-consciously varied list (you have to wonder if entries like ‘bazaar’ and ‘feast’ have been added in jest) speaks to the range of media that contributors to Fluxus worked in. The freely interdisciplinary collection of art forms demonstrates why the group didn’t operate like a movement: there were no guiding aesthetic principles, no singular methods shared by its

participants. The activities of Fluxus are instead held together by something at the same time practical and idealistic: as a founding contributor George Brecht wrote, Fluxus wasn’t an artistic movement but rather ‘individuals with something unnamable in common [who] have simply coalesced to publish and perform their work.’ It was a group of friends, young avant-garde

artists of all walks of life who saw the benefit of coming together, not to start imitating styles but to support and interact with each other’s unique artistic visions.

- Read: Review of Aquasonic | an underwater concert at Sonica Glasgow

- Read: Q&A with Joel Cahen | founder of Wet Sounds, a series of underwater concerts

Fluxus as an attitude

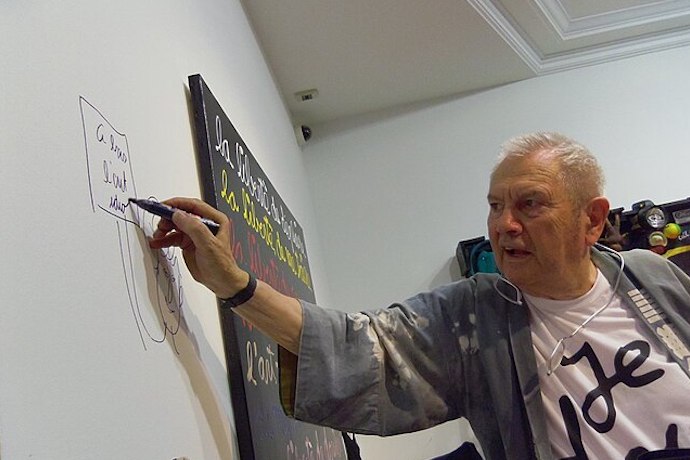

So, what is that ‘unnamable’ thing that Brecht so allusively refers to? Given the diversity of artworks that exist under the banner of Fluxus and its active resistance to categorisation, defining its principles isn’t easy. The list in the advertisement gives some indication. It shows a light-heartedness and irreverence, jokingly trailing off into a series of ‘et cetera’s like the writer got bored mid-sentence, and placing established cultural spaces like concert halls and exhibitions alongside democratic and participatory street events and demonstrations. As an early contributing artist Ben Vautier wrote, Fluxus is ‘light and has a sense of humour’. He also said that it ‘is the creation of a relationship between life and art.’ Whilst this is a slightly vague and grandiose statement, it does point to one of the defining principles of Fluxus: finding and making art out of the mundane. This ties in with both the humorous and the anti-establishment. There is an inherent absurdity to normal objects and actions being presented as artworks. This is simultaneously a more serious challenge to an establishment, which seeks to define what art can and cannot be.

- Read: Composers’ hobbies | what did Prokofiev and Cage do for fun?

- Watch: Interview with Alexandre Cellier | a multi-instrumentalist who plays piano, percussion, flutes, balafon, kalimba, hang, steel pan and 30 other instruments

Fluxus artwork

Let’s consider a Fluxus work by Vautier himself – ‘Total Art Matchbox’, from 1965. To create it he labelled a standard match box with the instructions that the matches inside should be used to burn every existing work of art, the last being used to destroy the matchbox itself. Here we see all the attitudes discussed at play. There is a humorous absurdity to the idea of anyone actually carrying out Vautier’s instructions. There is also a subversive quality to the artist taking a totally mundane object like a matchbox and turning it into an artwork which now sits in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This is itself is

wonderfully ironic, given that the work directly suggests that the contents of every gallery, MoMA included, ought to be destroyed.

‘Total Art Matchbox’ is just the tip of the Fluxus iceberg, and each work under its banner explores these and other related ideas in a totally unique way. The real richness of Fluxus lies ultimately in the art itself, and the radical, light-hearted, democratic, and disruptive vision of the world it suggests. Though all the artists involved in its initial exploration have since died, the attitude of Fluxus and the vision of life and art that they developed lives on, bound to no historic ‘movement’. ![]()