Museum of London, Barbican

By Harry Burgess

History is not just another name for the past; it is the name for stories about the past. How those stories are told is important. But, perhaps more important still, is who those stories are told by.

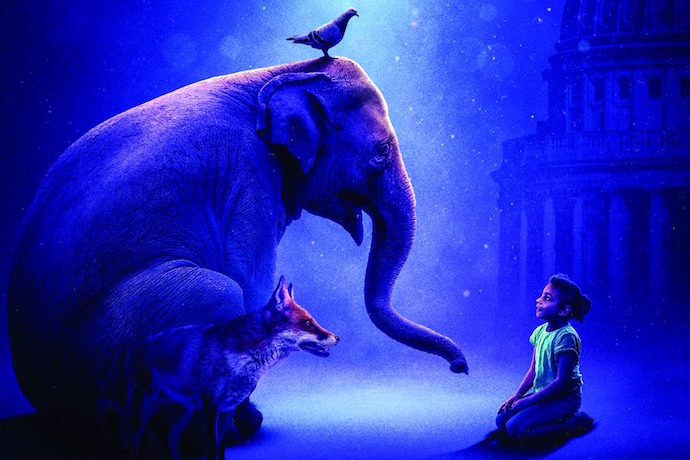

You won’t find any human narrators in Beasts of London—unless of course you mean the impressive cast of actors who’ve lent their vocal talent to the production. No: instead, you’ll learn about the colourful history of London straight from the horse’s mouth, as it were. In this exhibition-cum installation, the only narrators are the animals themselves. And the way they chronicle their individual stories—bringing to life prehistoric plains, medieval menageries, and sadistic circuses—is what makes Beasts of London so enthralling.

The exhibition is best described as multi-sensory and cross-disciplinary; the result of a collaboration between the Museum of London and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. After a short wait at the entrance, you enter. A few wan lights dot the perimeter of the asymmetric layout, interrupted at intervals by animated projections and related artefacts from the Museum’s collection. The music—at times brash, often delicate—commingles with bright illustrations of animals on the curved walls. The central corridor, where you first enter, splits off into separate rooms.

Each room features an episode plucked from the history of London: a holographic terrier, Tiny the Wonder, expounds on the virtues of rat baiting in a Victorian-era pub; horses, animated and projected onto three panels, tell us of their distinguished lineage in a room fitted with fairy lights and carousels; the apothecary’s room, jar specked and replete with skeletons and specimens, chronicles the history of the Plague in London.

I have no doubts that Beasts of London will appeal to both kids and adults. For kids, because it tells a fun story, has plenty of humour, and is filled to the brim with visual and aural delights (at times even interactive). For adults, the appeal will be part curiosity—who knew there was a Royal Menagerie in the Tower of London? or that London Zoo sold Jumbo the Elephant to P.T. Barnum’s circus?—and part quandary—what responsibility do we have to the welfare of animals? and how can we do better?

Leaving the exhibition, I noticed two pigeons flying overhead; regarded a bee that mistook my yellow coat for a flower; spotted a fox surreptitiously leaping into a garden to avoid a passing car. I was disappointed—life would be so much more interesting if animals could talk. ![]()

Beasts of London is showing at the Museum of London until 5 January 2020