Barbican Art Gallery, London

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou

It is fitting that the first large-scale exhibition in the UK of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work begins with a track by Duke Ellington. ‘Riding on a Blue Note’, composed by Ellington and originally played by his orchestra in 1927, could easily have been the background music to Tamra Davis’ 1985 film of a young Basquiat dancing in his studio. For Basquiat was known to listen to Jazz greats like Ellington, Gillespie and Parker when painting. He was also known for allowing the flow, flair and notational language of Jazz to spill onto his vibrant canvases. Such are the facts that the Barbican’s show, Basquiat: Boom for Real, paints anew.

Charting Basquiat’s development from graffiti to collage to paintings, the exhibition highlights the importance of music – or simply sound – to his artistic practice. Room 1 demonstrates this with a recreation of Diego Cortez’s 1981 group exposition, New York/New Wave, a show that virtually kicked-off Basquiat’s career as a commercial painter. Cortez saw New York/New Wave as a gathering together of ‘the detritus of the music’ scene, with iconic figures like David Byrne and Kathy Acker. But what hits the eye and ear in the Barbican’s rehang is Basquiat’s privileging not of musical sounds, but those of the street. In Untitled (1980), a scrap metal sheet sprayed yellow features child-like doodles of an aeroplane and car. Raining from the plane are clashing vowel sounds of ‘a’ and ‘o’. Rather than portraying the ‘detritus’ of the music scene, Basquiat’s Twomblyesque work celebrates the joyous cacophony of the city, with this piece in particular looking back to his subversive SAMO© scribblings of 1978.

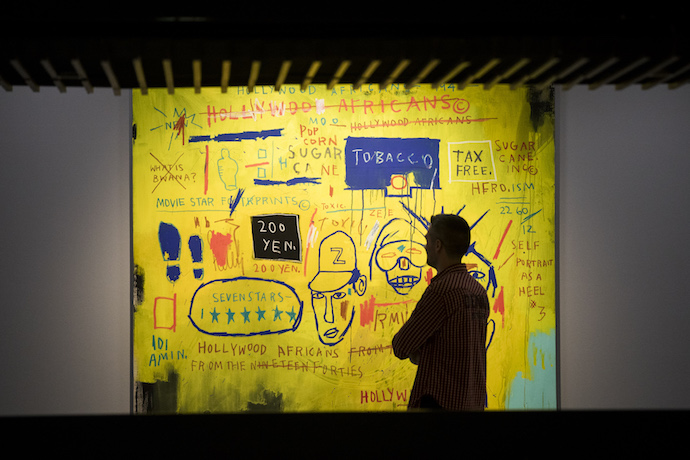

Yet musical sound, especially that of jazz and hip hop, took centre stage in Basquiat’s later paintings. In Hollywood Africans (1983), he personalises criticism of the institutional racism in Hollywood’s film industry, positioning three portraits at the centre of America’s creative core: of himself and his friends, the rapper Toxic and the afro-futurist artist-rapper Rammellzee. Drawn in Madonna-blue against a gleaming background of Oscar-gold, the talented trio can no longer be ignored by the white establishment. Quite the opposite, as the underscored word ‘HERO.ISM’ to the right of the canvas suggests. And if the heroics of paint weren’t enough, Rammellzee and Basquiat went on to produce a rap record entitled ‘Beat Bop’.

But it is the paintings of Room 9, such as King Zulu (1986) and Plastic Sax (1984), that pronounce the heroism of musical figures, like Charlie Parker and Louis Armstrong. Basquiat confronts the hostility and prejudice they endured: signs and phrases are carefully etched into the canvases, their free-association summoning pivotal moments in American political history as well as those in Parker’s and Armstrong’s own stories. Set against backdrops of tear-inducing blue, these paintings reference the origins of African American music itself. And this is the ‘realness’ expressed in the onomatopoeic exhibition title, ‘Boom for Real’, a phrase often expressed by Basquiat. This is the reality his work explodes. ![]()