A drizzly afternoon in the final cadenza before Christmas and a blessed opportunity to escape the London crowds with a performance by the Royal Concertgebouw at the Barbican Hall. However, the treasured civility of the orchestral concert was shattered even before the music had begun.

In the upbeat to the opening piece, the Prelude to Wagner’s Meistersinger, an orchestral spokesperson appeared to announce that this performance was part of the a two-year initiative to visit all 28 member states of the EU, and emphasised the importance of celebrating what it means to be European. The political overtones were obvious, if not six months too late, and the majority of the hall burst into applause.

Although the liberal sympathies of musicians and orchestral administrators are no secret, it was nevertheless incongruous to evoke the grubby reality of exit negotiations with Brussels before the sublime achievements of Wagner, Mahler and Berg. Yet, this moment spoke to a common presumption that classical music stands for unity in the face of political or physical conflict.

There’s an issue when you focus on race and sexuality. Would you do the same if he were a white man? Would you be talking about his life?

One of the enduring symbols of German reunification is the ‘Ode to Freedom’ concert in Berlin on Christmas Day 1989, in which Leonard Bernstein led musicians from orchestras East and West in a celebration of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Twenty five years later, Berlin’s three major orchestras united for a ‘Welcome among us’ concert for refugees from Syria and other war-torn regions at the city’s Philharmonie.

Yet when Russian conductor Valery Gergiev, a supporter of Vladimir Putin, mounted an official concert in the ruins of Palmyra with the Mariinsky Orchestra and soloist Sergei Roldugin (a close friend of the Russian president, and found in the Panama Papers investigation to be the owner of multiple offshore companies) after the ancient Syrian city’s recapture by Russian-backed state forces, the British government decried it as ‘tasteless’.

Politics is never simple, and when music strays into its path, the results are not straightforward. Yet for some, it is not good enough to stick your head in the sand. In 1974, British composer Cornelius Cardew claimed that the intellectual avant-garde, epitomised by the music of Stockhausen, constituted cultural imperialism and perpetuated the suppression of the masses. Cardew’s socialist ideals compelled him in new musical directions, including the founding of the Scratch Orchestra, an amateur ensemble that fulfilled the maxim that art must be open to all.

Left-wing radicals persist today. The Marxist values of American composer and pianist Frederic Rzewski are explicit in works such as Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues, in which a worker’s folk song is engulfed by propulsive piano ostinati that evoke the industrial clamour of a factory, or his most famous work The People United Will Never Be Defeated, a set of variations on the Chilean revolutionary song. (In a neat moment of practising what you preach, Rzewski recently performed the hour-long work at a Pittsburgh fish market.)

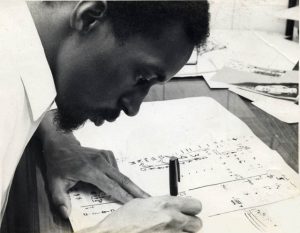

Musicians such as Cardew and Rzewski provide a powerful riposte against frequent accusations that classical music is elitist and oblivious to the social reality that surrounds it. So too does Julius Eastman, until recently a forgotten figure from the vibrant experimental New York scene in the 1970s and 80s.

First known as a baritone, particularly for his 1973 recording of Peter Maxwell Davies’ Eight Songs for a Mad King, Eastman caused a stir with free-wheeling works such as Femenine and Prelude To The Holy Presence of Joan D’Arc that combined the minimalism of New York contemporaries Steve Reich and Philip Glass with an uncompromising streak that didn’t shy away from atonality and hard-edged experimentation.

By the time of his death in 1990, aged 49, Eastman had fallen off the radar after problems with alcohol and drugs, and his scores were presumed missing. Yet after a flurry of recent discoveries, performances and recordings, interest in Eastman has reached fever pitch. For many in classical music, his sexuality and the colour of his skin are a welcome means of countering charges of a woeful lack of diversity.

‘His position as ‘black and gay’ is something that we feel might have become fetishized,’ warn Antonia Alampi and Bonaventure Ndikung, curators of a new exhibition on Eastman at SAVVY Contemporary as part of the Berlin Maerzmusik Festival. Indeed, certain tropes recur in recent writing on Eastman, including the anecdote of him performing John Cage’s Song Books and shocking the elder composer by undressing a young man on stage. Alampi continues, ‘There’s an issue when you focus on race and sexuality. Would you do the same if he were a white man? Would you be talking about his life?’

Eastman was far more than simply a provocateur, transgressing the unwritten rules of the experimental scene in the 1970s and 80s. His ‘Nigger Series’ may have attracted the majority of attention during the past few years of the Eastman renaissance, but has intellectual weight behind the controversial title. ‘I have no problem with the fact that people perform the series,’ says Ndikung, ‘but it needs to be contextualised. He had a reason.’

Eastman was forced to defend the series’ title after students protested performances of the works in the mid-1980s: ‘The reason I use that particular word is because it has a basicness about it. The first niggers were of course field niggers, which is the basis of the American economic system.’ He also stated that just as there are 99 names for Allah, ‘there are 52 words for nigger.’

Similarly, discussing his 1979 work ‘Gay Guerrilla’, Eastman asserted the importance of controlling his identity. ‘These names; either I glorify them or they glorify me. And in the case of ‘guerrilla’, that glorifies gay.’ For Ndikung, his political awareness was central to Eastman’s compositional practice. ‘Eastman was a political being, and cared about what was happening in his time. To me, that is an expression of a great artist; somebody that feels the pulse of his time.’

Julius Eastman took noisy and difficult positions contrary to many in his supposedly radical milieu. Yet the reason he continues to fascinate is because his music is not simply agitprop, but enriched by his principles. Crazy Nigger is propulsive and indignant, yes, but builds to an exuberant din that is affirmative and ecstatic.

The best political art is deepened, not simplified, by its context. Cardew’s The Great Learning, written for The Scratch Orchestra, remains fresh and unique nearly 50 years on, and Rzewski’s Coming Together, written to a text written by an inmate who died in the 1971 Attica prison uprising, is hair-raising. And whilst Gergiev’s Palmyra performance is ragged and glib, Bernstein’s reunification concert crackles with palpable emotion. Perhaps we need such radicals and idealists now more than ever. ![]()

‘Let Sonorities Ring – Julius Eastman’ opened at SAVVY Contemporary on March 16

MaerzMusik 2017 opens with Julius Eastman’s music for four pianos at the Haus der Berliner Festspiele on March 17

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IInG5nY_wrU